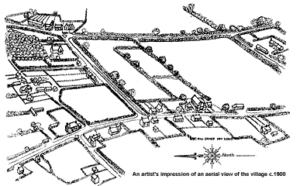

Breachwood Green, near Hitchin in Hertfordshire. Where I lived until I was seven in 1951. Today I’m stepping back in time and remembering what it was like in the nineteen forties.

Breachwood Green, near Hitchin in Hertfordshire. Where I lived until I was seven in 1951. Today I’m stepping back in time and remembering what it was like in the nineteen forties.

The cottage looked as if it had been brought to life out of a picture book. It had a front door in the middle, and one sash window each side. There were three sash windows upstairs. Come inside with me and have a look round.

There was a narrow passage that led past a room on our left and a room on our right. There were two doors at the end of the passage. If you opened one, you’d be faced with the stairs. I expect it was there because the cottage had once been a small pub, and you wouldn’t want the visitors to wandering about in the bedrooms, would you? The second door led to the kitchen, which I remember best.

What I’m going to tell you next will come as a great surprise. We didn’t have any taps inside the cottage. There was one just outside the house next door, and my mum or dad had to go and fetch all our water in metal pails. Of course, there was no toilet indoors either. Outside in the back garden, there was what was called a privy. It was a sort of shed, but the sort where you keep garden forks and spades and rakes. If you peeped inside you would see something like a long wooden box, fixed against the wall, with a smooth plank on the top. There were two holes in the plank, one for grown up bottoms and one for a child’s bottom. No flush of any kind. I expect a lot of readers are now feeling rather nauseous. If yes, skip the next bit.

Every so often my dad had to dig out the, erm, stuff in the box part, and cart it up the garden and bury it in a hole, I suppose. It must have been rather pongy I think, especially in a hot summer.

Anyway, let’s turn to something a bit less disgusting!

Not only was there no running water, there was definitely no central heating. My mum had to light the range in the kitchen every day, and make sure she had enough wood to get the fire going in the morning. There was a big woodstore next to the house, and sometimes I’d watch my mum chopping the wood. I’ve never liked axes, and I think Mum may have warned me never to touch hers or even come close while she was chopping.

It must have been a hard life in many ways, but for a little girl of four, five or six, it was wonderful. In spring the countryside was full of birdsong, and I remember running along the lane to peep into a robin’s nest in the bank.

My mum had shown it to me. You can guess how sad we were to find, one day, that it had been destroyed. Mum said that boys sometimes did that sort of thing. They’d probably taken the eggs for their collections.

My mum had shown it to me. You can guess how sad we were to find, one day, that it had been destroyed. Mum said that boys sometimes did that sort of thing. They’d probably taken the eggs for their collections.

When I was about six or seven, my mum and dad bought me a bike, second hand I expect. You have to understand that there wasn’t much traffic in those days, someone on a bicycle perhaps, the odd tractor. Mum took me out on fine days, and this is how she taught me to ride. She had one hand under my saddle to stop me falling off, and the other hand steadying my little brother, who was about two or three. I wobbled a lot at first, but my mum’s hand under the saddle held me firmly upright. One day I rode along, chatting away to my mum, yak, yak, yak. Then I asked her a question. Why didn’t she answer? I looked back and nearly fell into the road. She was a long way behind, seeing to my brother who had fallen over and hurt himself. I was riding my bike all by myself!

When I was about six or seven, my mum and dad bought me a bike, second hand I expect. You have to understand that there wasn’t much traffic in those days, someone on a bicycle perhaps, the odd tractor. Mum took me out on fine days, and this is how she taught me to ride. She had one hand under my saddle to stop me falling off, and the other hand steadying my little brother, who was about two or three. I wobbled a lot at first, but my mum’s hand under the saddle held me firmly upright. One day I rode along, chatting away to my mum, yak, yak, yak. Then I asked her a question. Why didn’t she answer? I looked back and nearly fell into the road. She was a long way behind, seeing to my brother who had fallen over and hurt himself. I was riding my bike all by myself!

This is post office (left) and The Red Lion in Breachwood Green in1946, when I was two.